The Gobbins' dreamlike landscape – created through immense geological forces, carved by the elements, teeming with life – has inspired visitors for over a century. Discover how nature formed this unique place and how a nineteenth-century visionary gave ordinary people a chance to experience it for themselves.

200 million years in the making

The Gobbins’ Story begins some 200 million years ago when the Earth looked very different to today. Then, all the landmasses were fused in a single continent called Pangaea. The land that would become northeast Ireland lay beneath a warm and shallow sea. Over aeons, layers of sand and mud accumulated into rock.

By one hundred million years ago, this region still bathed in a shallow, tropical sea. Now, however, it teemed with life. The most abundant organisms were algae and single-celled organisms encased in calcium carbonate shells.

Countless generations of these shelled animals lived and died, depositing layers of calcium on the seafloor. It solidified over time into a limestone layer found on coastlines and in caves across Ireland. This stone forms the foundations of the Gobbins’ stunning rock formations. You can see an outcrop of it today – look south to Hills Port as you descend to Wise’s Eye.

By one hundred million years ago, this region still bathed in a shallow, tropical sea. Now, however, it teemed with life. The most abundant organisms were algae and single-celled organisms encased in calcium carbonate shells.

Countless generations of these shelled animals lived and died, depositing layers of calcium on the seafloor. It solidified over time into a limestone layer found on coastlines and in caves across Ireland. This stone forms the foundations of the Gobbins’ stunning rock formations. You can see an outcrop of it today – look south to Hills Port as you descend to Wise’s Eye.

These eruptions also laid down the basalts now exposed along the Gobbins’ cliff face. These cliffs are just the easternmost edge of a basalt structure that stretches from Cave Hill, near Belfast, to Binevenagh Mountain in County Londonderry.

Volcanic activity has long finished, but Northern Ireland’s landscape continues to be sculpted by tectonic and climatic forces. Fracturing, caused by the ongoing movements of continental plates, has cracked and shifted the bedrock. Lough Neagh is just the largest structure this constant pressure has created. Wind, rain and sea scoured the mountains.

These eruptions also laid down the basalts now exposed along the Gobbins’ cliff face. These cliffs are just the easternmost edge of a basalt structure that stretches from Cave Hill, near Belfast, to Binevenagh Mountain in County Londonderry.

Volcanic activity has long finished, but Northern Ireland’s landscape continues to be sculpted by tectonic and climatic forces. Fracturing, caused by the ongoing movements of continental plates, has cracked and shifted the bedrock. Lough Neagh is just the largest structure this constant pressure has created. Wind, rain and sea scoured the mountains.

Great ice sheets spread south from the Artic beginning almost two million years ago. Their colossal weight and constant movement wore away the landscape even faster, carving out the Glens of Antrim and the rolling hills of the plateau. Recent ice ages have seen ice sheets spread and retreat, each time leaving sand, gravel and boulders strewn across the landscape. Moreover, they have left the Antrim Coast relatively unstable – landslips frequently occur along the Antrim Coast Road and posed severe challenges to the Gobbins Cliff Path’s engineers.

They also helped carve out the extraordinary rock formations that provide numerous habitats for various birds and sea life. For example, the Gobbins is home to Northern Ireland’s only mainland colony of puffins, which burrow into the cliff-side soils churned up by the glaciers.

Guillemots, razorbills, cormorants, and kittiwakes make their homes high in the rocks and scan the waters from perches on the sea stacks. The depths teem with fish, feeding in the plankton-rich waters of the North Channel. Lions Mane jellyfish, one of the largest such species, migrate through here, providing prey for seals, porpoise and other marine mammals.

Low tide exposes the rockpools under the path, a home for molluscs, sponges and weird nodules of red seaweed. Spleenwort ferns, kidney vetch, and sea campion clings to cracks in the rocks or hold down patches of volcanic soil.

This natural beauty drew many admirers, especially in the nineteenth century when naturalists and day-trippers began to visit the Antrim coastline.

They also helped carve out the extraordinary rock formations that provide numerous habitats for various birds and sea life. For example, the Gobbins is home to Northern Ireland’s only mainland colony of puffins, which burrow into the cliff-side soils churned up by the glaciers.

Guillemots, razorbills, cormorants, and kittiwakes make their homes high in the rocks and scan the waters from perches on the sea stacks. The depths teem with fish, feeding in the plankton-rich waters of the North Channel. Lions Mane jellyfish, one of the largest such species, migrate through here, providing prey for seals, porpoise and other marine mammals.

Low tide exposes the rockpools under the path, a home for molluscs, sponges and weird nodules of red seaweed. Spleenwort ferns, kidney vetch, and sea campion clings to cracks in the rocks or hold down patches of volcanic soil.

This natural beauty drew many admirers, especially in the nineteenth century when naturalists and day-trippers began to visit the Antrim coastline.

Right man.

Right place.

Right time.

Berkeley Deane Wise was passionate about safety. That might seem strange for a man who built bridges between sea cliffs, but it was his commitment to quality that made The Gobbins possible.

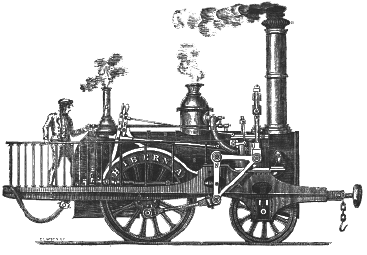

He was a solicitor’s son from County Wexford and a member of the growing Victorian middle class – raised in Dublin and schooled in England. He began his civil engineering career in 1872, working on the Navan and Kingscourt Railway. It was an exciting time to be an engineer. Industrialisation was in full swing, and factories were producing scores of new consumer goods. Rail travel and the telegraph cut distances. Ordinary people were enjoying a host of new possibilities.

Wise distinguished himself early in his career, and by 1877 he was the Chief Engineer of the Belfast and County Down Railway. At this time, he developed an innovative signalling system that reduced collisions on his lines – tragically not uncommon in the 19th century.

He became Chief Engineer on the Belfast and Northern Counties Railway in 1888. In this role, his passion for safety and the exuberance of his age inspired his finest achievements in bringing mass tourism to the Antrim coast. Leisure travel for ordinary people was a new phenomenon at the turn of the last century. Never before had so many people had so much free time, and the railway gave them exciting ways to use it.

Wise saw that the Antrim coast offered spectacular landscapes and bracing experiences within easy reach of Belfast. He built railway stations with fascinating architectural flourishes, like the mock Tudor building and clock tower in Portrush. He constructed paths, walkways and a tearoom in Glenariff Forest so that people could view its woods and waterfalls. He erected the promenade and the bandstand at Whitehead and imported sand to lay down a beach there.

The Gobbins Cliff Path is his most important contribution. It best embodies his genius as an engineer working to help ordinary people enjoy extraordinary experiences. Construction began in 1901, and the first section – a pathway from the nearby village of Ballystrudder to the base of the cliffs – opened in August 1902. Wise’s vision of tunnels and bridges spanning the cliffs was more challenging to realise. The steel girder bridges were built in Belfast, brought to Whitehead on barges and manoeuvred up the coast on rafts. Workers winched them into place on lines dropped from the clifftop.

The Gobbins Cliff Path is his most important contribution. It best embodies his genius as an engineer working to help ordinary people enjoy extraordinary experiences. Construction began in 1901, and the first section – a pathway from the nearby village of Ballystrudder to the base of the cliffs – opened in August 1902. Wise’s vision of tunnels and bridges spanning the cliffs was more challenging to realise. The steel girder bridges were built in Belfast, brought to Whitehead on barges and manoeuvred up the coast on rafts. Workers winched them into place on lines dropped from the clifftop.

The path was an overnight success, attracting visitors from across Ireland and Britain, many coming on a steamer to Larne. It was said to be busier than Royal Avenue – one of Belfast’s central shopping streets – as visitors pushed past each other to see the next sight.

The Path Reimagined

Fifty years later, Larne Borough Council announced an ambitious plan to reopen The Gobbins. They constructed fifteen new bridges and six elevated paths using the latest materials and working to modern health and safety standards – an approach that Wise would have approved.

While the methods may have changed, the design has remained the same. The Gobbins’ engineers built replicas of the Tubular Bridge and the suspension bridge at the Seven Sisters to retain the charm of its original, Edwardian design.

The path reopened in 2015 and now attracts tens of thousands of visitors each year. Mid and East Antrim Borough Council, The Gobbins’ current custodians, are laying plans for an extension that will realise Berkeley Deane Wise’s original vision.